At the current rate, more than 140,000 people in Washington’s state could be living with Alzheimer’s disease by 2025, researchers estimate.

“What we’re dealing with is nothing less than a public health epidemic,” according to Bob Le Roy, executive director for the Alzheimer’s Association Washington State Chapter.

Researchers with the association say the disease — the only fatal form of dementia — is Washington’s third leading cause of death, and costs taxpayers nearly $500 million each year in Medicaid costs.

Despite the dour numbers, local advocates and state officials say there’s hope ahead.

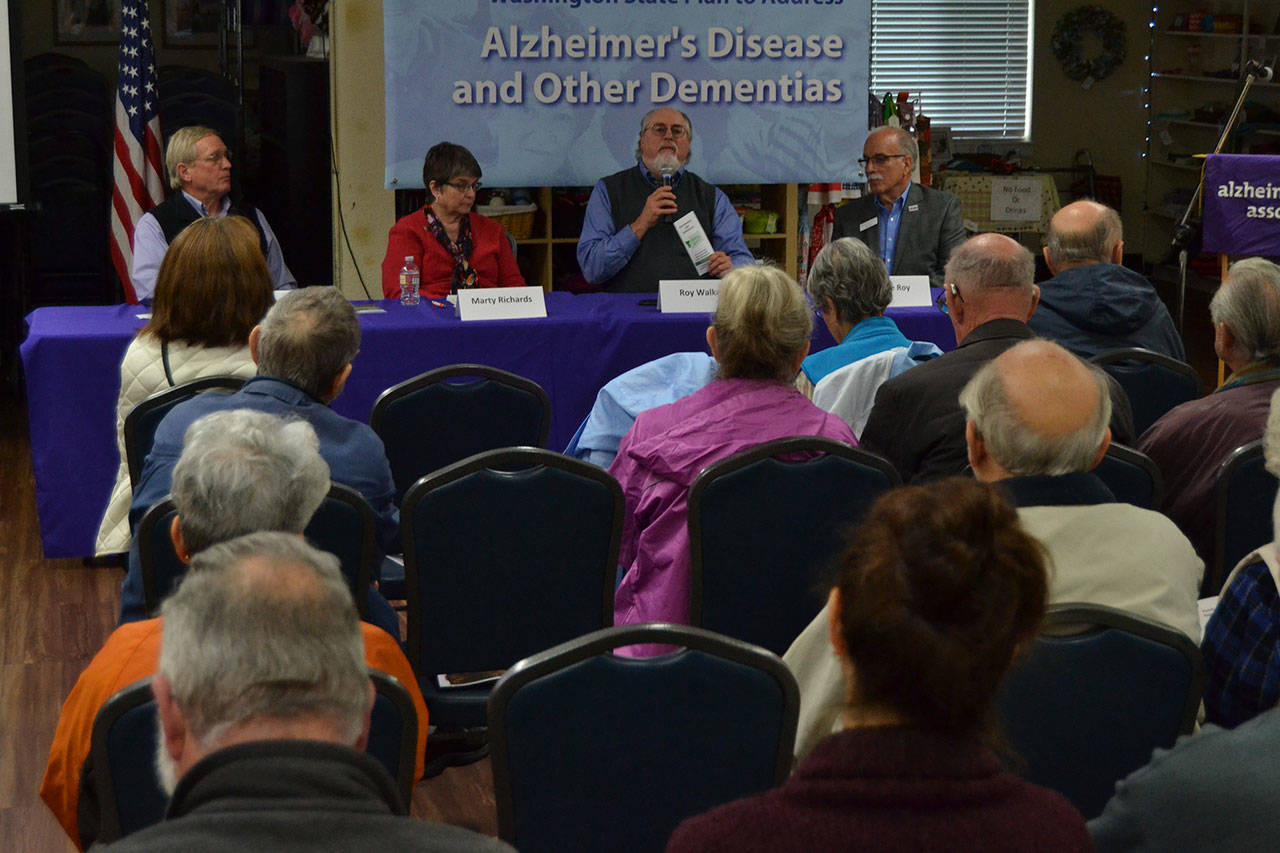

At a town hall on Oct. 8 at the Shipley Center in Sequim, Le Roy and other Alzheimer’s research and care advocates spoke to a crowd of about 30 about the Dementia Action Collaborative’s efforts to implement Washington’s plan to connect people with resources while seeking more research and services support.

Le Roy said the Alzheimer’s Association is asking the state legislature for $5.4 million in 2019 to promote public awareness and engagement about aging, warning signs of dementia and the value of early diagnosis.

“It’s often harder to make the first connection,” he said. “There are resources people are just not aware of.”

Connections

Alzheimer’s Association leaders estimate more than half of Washingtonians who reported their memory loss is getting worse have not spoken to a health professional about their symptoms.

Part of the funding request includes promoting early legal and advance care planning, sharing dementia best care practices with primary care practitioners, developing a Dementia Care Specialist program, and more.

State representative Steve Tharinger, one of the Town Hall’s panelists, said state leaders have been “moving forward incrementally with support, but we’re starting to see success on a number of these fronts.”

One effort includes the “Dementia Road Map” pamphlet that Tharinger said has been “extremely helpful for people starting out with an early diagnosis.

“What do you do? What do you do legally? It moves you through the process as the disease progresses,” he said.

“That basically came out of caregivers and patients in the (Dementia Action Collaborative).”

Le Roy said since 2016 advocates have distributed more than 40,000 copies of the Road Map.

Panelist Marty Richards, who holds a masters degree in social work, said the Collaborative has been one of the most exciting times in her career.

“We want to put an emphasis on what people can do, not just talking about what people can’t do,” Richards said.

One effort has been establishing Alzheimer’s cafes for people with dementia to meet and feel accepted.

One cafe meets at 3 p.m. the fourth Thursday of each month at Ferino’s Pizzeria in Port Hadlock.

Sequim Bible Church, 847 N. Sequim Ave., also hosts an Alzheimer’s Association caregivers support group from 1-2:30 p.m. on the second Thursday of each month, with its next meeting on Nov. 8.

Roy Walker, director of Olympic Area Agency on Aging, and a panelist at the Oct. 8 event, said progress in fighting Alzheimer’s disease involves advocacy.

“We continue to tell our electorates that its important to focus on this issue,” Walker said.

“That we want this to be a priority. We want money to go towards the research. We want support for caregivers.”

Tharinger agreed saying activism and voting are important.

He added that Washington spends about $6 billion on long-term adult care and it’s not meeting the need.

“That’s why this dialogue is important,” Tharinger said.

Long-term care

Alzheimer’s Association staff say in 2016, 335,000 family members in Washington state provided free caregiving for loved ones at an estimated cost of $4.8 billion over 382 million hours.

Several panelists reiterated that Medicare does not pay for long-term care and that many people — about half the population — do not have enough saved for future care.

One solution Alzheimer’s Association staff spoke about is The Long-Term Care Trust Act, a measure up for consideration in 2019 in the legislature. It would create a benefit workers ages 18 and older can opt into, with provisions to save for personal care, medical assistance, transportation and more.

“The Legislature is looking to build a safety net that provides a continuum of care,” Tharinger said.

“It’s a huge challenge to figure out a system that works. We’re going to have to put more dollars into this system.”

Le Roy said advocates for the house and senate bills are looking into whether or not retirees can buy in quicker to the saved funds despite a required 10-year vesting period.

To effectively treat and prevent future cases of Alzheimer’s disease by 2025, Le Roy said, the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s states researchers need $2 billion a year to meet the goal.

Last year, about $1.9 billion was made available for research and support, which Le Roy said tripled from 2015.

The Alzheimer’s Association offers a 24/7 support line at 1-800-272-3900 with clinical social workers on-hand. Find more information online at www.memorylossinfowa.org and www.alzwa.org.

Read the Dementia Road Map here.