This COVID situation reminds many of us of growing up in Sequim during the 1940s or ’50s during the frightening Polio epidemic. It was thought to be spread through water, so some beaches were closed to the public, parents warned their kids not to swim in the irrigation ditches and the Port Angeles swimming pool on Peabody Street was closed.

My swimming lessons were interrupted so I blame the disease, not the swim coach, Bill Shore, for my lack of mastering that needed skill.

Many Clallam County children were stricken decades earlier during the first wave of the horrible disease, but this time we had friends and classmates end up in iron lungs in Seattle (Children’s Orthopedic Hospital), a terrible nightmare for many local families.

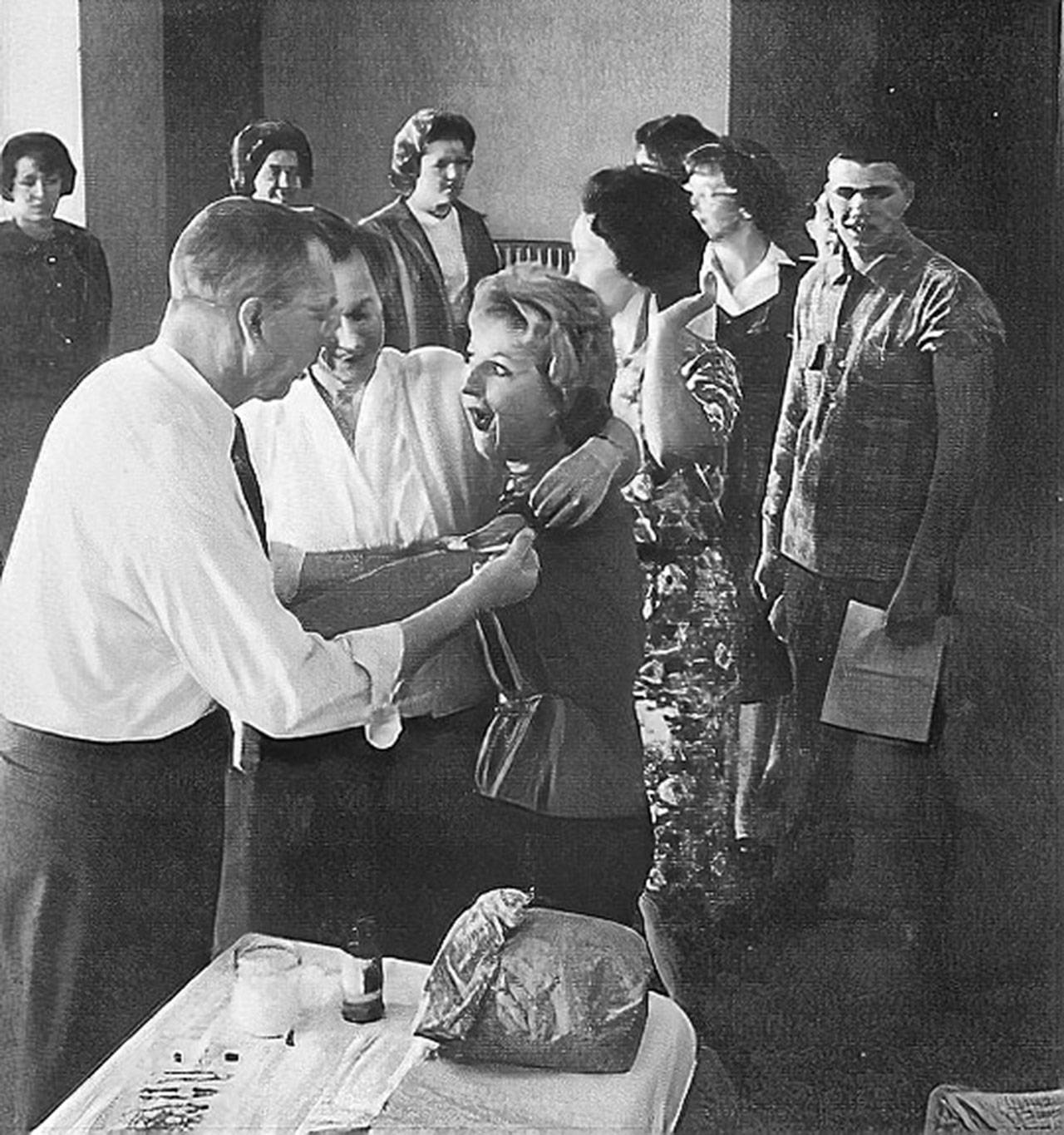

Sometime in 1961, we were taken by class to the newly built Sequim High Gymnasium to wait in line for some unknown reason that became apparent as we got closer. My close friend Lois Trudel let out a blood-curdling scream when the big needle hit her upper arm that scared me enough to back up against the door. But there was no escape, with principal and Mr. Beil and Mr. McClurken blocking the exits. Mr. Copeland, Mr. Schade and other teachers encouraged any runaways to get back in line.

I vividly remember the wait for nurse Hubbard to hand each loaded needle to a strange man (I hope he was a doctor) who gave the pain. This was not just any shot — this was the Salk Polio Vaccine, that went in slow with a really big needle that seemed to take forever to remove.

Remember, this is the memory of a 17-year-old girl surprised during a normal history class, only to get back to class to find out our parents had no prior warning, either.

We protected our sore arms the rest of the day, the incident was recorded in our shot record; at the nurse’s office and that night we let our parents know at the dinner table of our vaccination.

They were just thrilled; they called the grandparents, friends and neighbors to share the wonderful news of the new scientific miracle to protect their children from being paralyzed.

We whined about a sore, hot, inflamed arm for a week but don’t remember any of us getting other side effects.

Polio was eradicated in the world in the early 1960s with the genius of Dr. Jonas Salk, who used his own young son along with the children of Public Health Service doctors and nurses, during the clinical trials.

Judy Reandeau Stipe is the volunteer executive director of Sequim Museum & Arts. This article was originally published in The Prairie Review, the Sequim Museum & Arts newsletter, and reprinted here with permission.