by MARK ST.J. COUHIG

Sequim Gazette

(Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series on the financial difficulties facing the law and justice communities in Clallam County and the City of Sequim.)

During their Monday, Oct. 1, debate, Clallam County Commission candidate Maggie Roth mostly agreed with her opponent in the race, incumbent Mike Chapman.

The one glaring exception concerned new taxes.

Roth, a Republican, said she’s in favor of giving voters an opportunity to vote on a new “Law and Justice Tax” that would help pay the county’s mounting criminal justice costs.

The funds would support not just the sheriff’s office, she said, “but the courts, jails and prosecutors.”

“Somehow we’re going to have to find tax revenues.”

Chapman, a former Republican and now an Independent, said the voters already have spoken, telling the commissioners to live within their means.

“I may be the only (office holder) ever criticized for not moving on a new tax,” he said. He added that the county has reserves equal to approximately a third of the annual budget. “Why should we raise taxes?” he asked.

But Chapman also has been careful to note that he isn’t ruling out forever the need for a new law and justice tax.

“No one would ever say that,” he said. “But people are hurting right now. We would need to see a unified coalition supporting it.”

Stopgap efforts, including employee furloughs and drawing from the reserves, have left the budget balanced. But the unified coalition may be building as the rising costs of criminal justice are having a profound impact on county finances.

Statewide worries

County Administrator Jim Jones said Clallam isn’t unique. “We see a long pattern of rising law and justice costs around the state — pretty much all counties.”

The costs are increasing at two to three times the rate of inflation, Jones said.

He says he knows where the blame can be laid. “The legal system and the Legislature are putting costs onto the system that end up costing an arm and a leg.”

Jones noted that in Washington the bulk of the burden for prosecuting crimes goes to the county. “A very small amount is paid by the state,” he said.

He provided a brief history to illustrate the issue, noting that in the mid-2000s the Washington Legislature passed a law limiting the amount that property taxes can be raised to 1 percent per year. That worked fine from 2005 through 2008, he said, as the state enjoyed “one of the biggest building booms in history.”

“Enter 2008 and the big crash,” he said.

With little new building going on, the county now has to live with a 1-percent increase in property taxes on existing structures. Meanwhile, Jones said, “inflation is 3 to 3.5 percent” and the cost of the criminal justice system is climbing at a rate “three to four times” that.

Some of the increase can be attributed to a change in the definition of “indigent,” which is used to determine who is eligible for a publicly funded defense. Under the new rules, Jones said, “If a person says, ‘I would like a public defender,’ they get one.”

As a result, “Maybe 99 percent of felony defendants are using public defenders,” Jones said. “If you’re a crook — a felon — it’s entirely paid for by county.”

That change will be exacerbated next year when new rules are put into place reducing the number of cases a public defender can handle. The county will be responsible for enforcing the new limits.

Counties also are responsible now for paying for the medical care of those they have jailed.

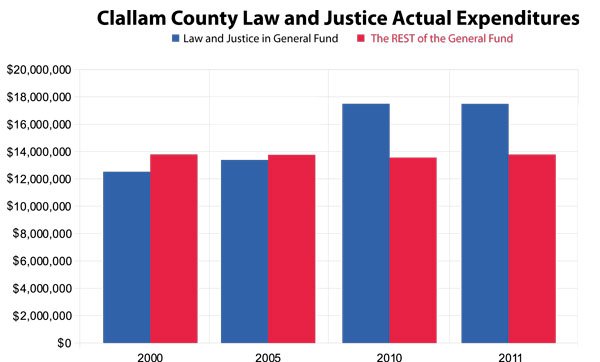

Currently 70 to 75 percent of the county budget goes to support the justice system. “It could be as high as 100 percent and that still wouldn’t be enough,” Jones said.

“One murder trial could literally bankrupt a small county,” he said. “And we’re sitting on five right now. We’ve got to figure it out.”

A little history

Jones said several years ago the Legislature “came to the rescue,” passing a new law that allows counties and municipalities to impose a “public safety tax,” now more commonly called a “law and justice tax.” The tax can range up to 3/10 of 1 percent on sales.

That was a boon, Jones said. “The nice thing about sales tax revenue is that it’s adjusted for inflation.”

At that point Clallam County and local officials began discussions regarding the possibility of putting the tax before voters. But they declined to move on it, believing the economy would soon improve. They also were skittish about spending the $70,000 to $90,000 it would cost to hold the election.

They decided to “wait until we have the crisis,” Jones said.

In October 2011, the crisis hit. The county, staring a $2.7 million deficit in the eye, was planning to lay off 35 employees, some of them working in law and justice offices.

The Clallam County Law and Justice Council, which includes representation from the cities, was asked to consider the tax.

“The cities said, ‘We don’t support it.’” Jones said.

The county commissioners don’t need the support of the cities, Jones noted, “but if the cities come out against it, the people won’t vote for it.”

The county’s unions came to the rescue, saying they would agree to furloughs and two years with no cost-of-living raises.

“It was an honest-to-God actual cut for everybody but those in law and justice,” Jones said. “Everyone else took the 6.15-percent cut.”

The county recalled the layoff notices.

Jones said many members of the law and justice community then decided the crisis was over. “They weren’t supportive of the tax,” he said.

“It’s a complicated circle.”

Jones said other counties already have begun making cuts in their law and justice budgets. “In 2009, King County laid off deputies and deputy prosecutors. We didn’t cut any.”

“But we didn’t let them grow and they screamed bloody murder.”

Jones said simply attempting to hold the line on the budget may be insufficient. “In my opinion there’s no substantive place in all the rest of the county to cut. (Law and justice is) all that’s left.”

“We have to ask the voters: Do you agree to these cuts or do you agree to new taxes?”

Reach Mark Couhig at mcouhig@sequimgazette.com.