Sequim scientists are turning algae inside out to find the best and cheapest biofuel possible in a new way.

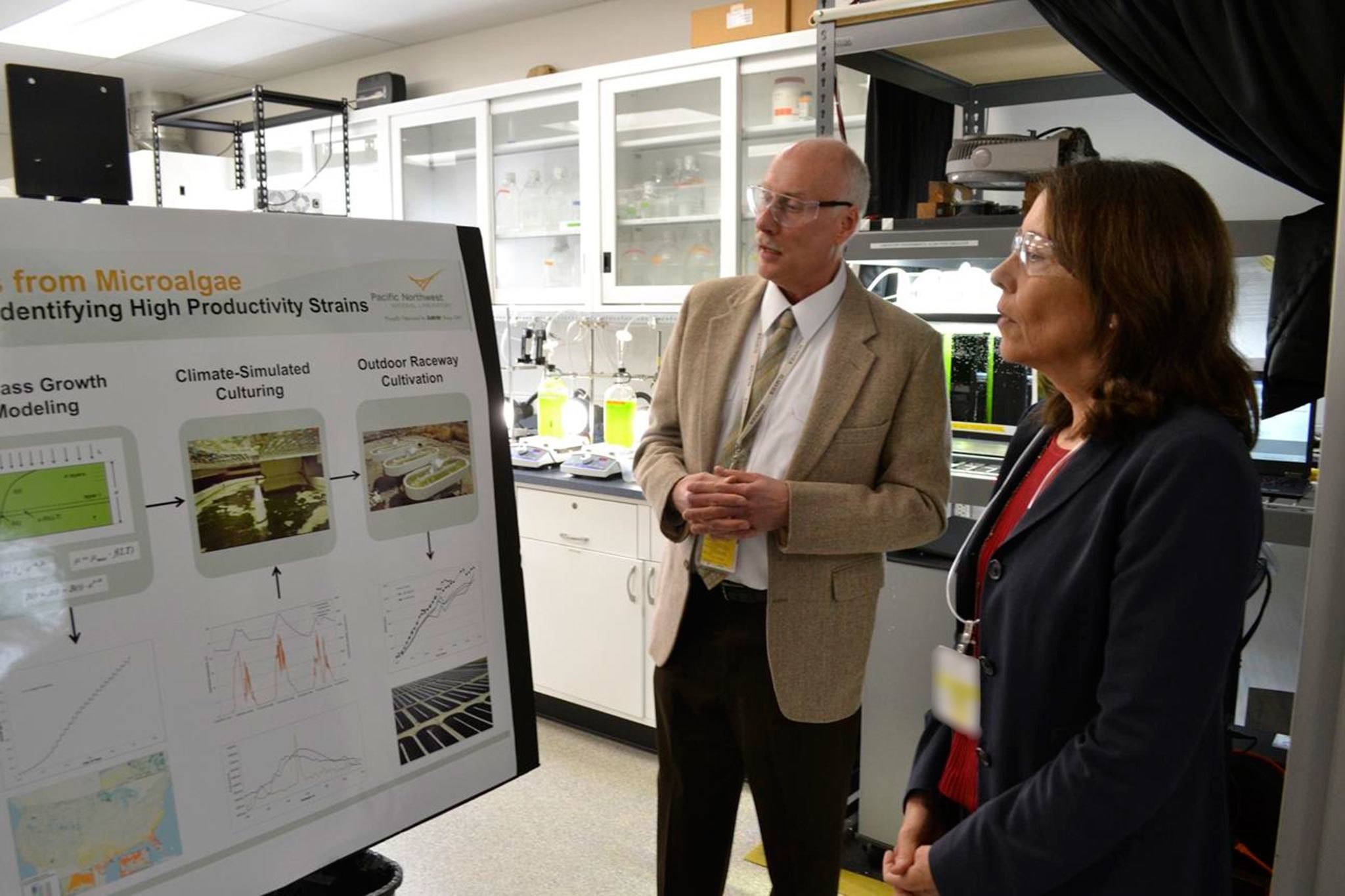

Dr. Michael Huesemann, a lead researcher at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s Marine Sciences Laboratory in Sequim, said algae is a promising clean energy but currently expensive to harness effectively.

“The price of biofuel is largely tied to growth rates,” he said. “Our method could help developers find the most productive algae strains more quickly and efficiently.”

Huesemann, who has worked with algae for 16 years, started on the $6 million, three-year algae DISCOVR project, Development of Integrated Screening, Cultivar Optimization and Validation Research, in October 2016 with a small team of senior and junior scientists in Sequim.

“What we’re really interested in are carbon neutral biofuels that can be grown in the United States,” he said.

“We haven’t found any algae that grows fast enough or provides enough biofuel so we’re trying to find microalgae that grows fast to make biofuels.”

Huesemann said there are millions of strains in nature to sort through so rather than a “shotgun approach and randomly screening” they are “doing an organized, rational screening.”

Process of elimination

Finding the best algae is broken into a process of five tiers between labs in Sequim, three other Department of Energy labs — Los Alamos National Laboratory, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories and Arizona State University’s Arizona Center for Algae Technology and Innovation.

Previously, researchers tried to evaluate algae in test tubes, but find lab results don’t always mirror outdoor ponds, laboratory officials said.

In Tier I, scientists in Sequim and New Mexico test up to 30 different algae strains to see how weather tolerant they are and the top third will go to Tier II, Huesemann said.

In Tier II, Sequim houses a unique climate-simulating system called LEAPS, Laboratory Environmental Algae Pond Simulator, that simulates climates and seasons around the world inside glass cylinder photobioreactors.

Two other labs will evaluate the algae to see if there is any value in its compounds that could be used for products like food dye phycocyanin, which could make algae biofuel production more cost-effective, Huesemann said.

Scientists also will research how resilient certain algae strains are to predators, like protozoans, and other competing algae.

Huesemann anticipates Tier I and II being conducted this year, he said.

For Tier III, researchers in New Mexico will further test top-performing algae strains, Huesemann said, which includes “forcing cells to grow faster or generate more oils, using state-of-the-art laboratory techniques such as directed evolution and fluorescence assisted cell sorting.”

Afterward, strains will travel to outdoor ponds in Arizona for study as part of Tier IV to compare biomass output with earlier steps. Lastly, scientists will study the algae strains that performed the best in different lighting and temperature conditions for Tier V.

Data will go into the Pacific Northwest National Laboratories’ Biomass Assessment Tool to help researchers generate maps that illustrate the expected biomass productivity of each algae species grown in outdoor ponds “all over the U.S. in different seasons on any day of the year,” Huesemann said.

Once the study is complete, research will be made public for companies and other researchers.

Laboratory officials said work that could stem from this project includes converting harvested algae into biofuels, examining operational changes such as crop rotation to further increase biomass growth and assessing the technical feasibility and economic costs of making biofuel from algae selected through this process.

For more on the experiment, visit http://www.pnnl.gov/news/ or http://marine.pnnl.gov/.