A better fuel for tomorrow could soon be floating along the West Coast.

Officials with the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory recently announced it received funding to investigate making seaweed, or macroalgae, into biofuel from a new autonomous rope system that floats along the ocean.

“It’s exploring the last frontier,” said Dr. Michael Huesemann, lead researcher for the algae biofuel program in the Marine Sciences Laboratory in Sequim.

“Our planet covers 70 percent of the surface area but only supplies 1 percent of the world’s food or biomass. This doesn’t compete for food and it’s all from the ocean and uprising nutrients.”

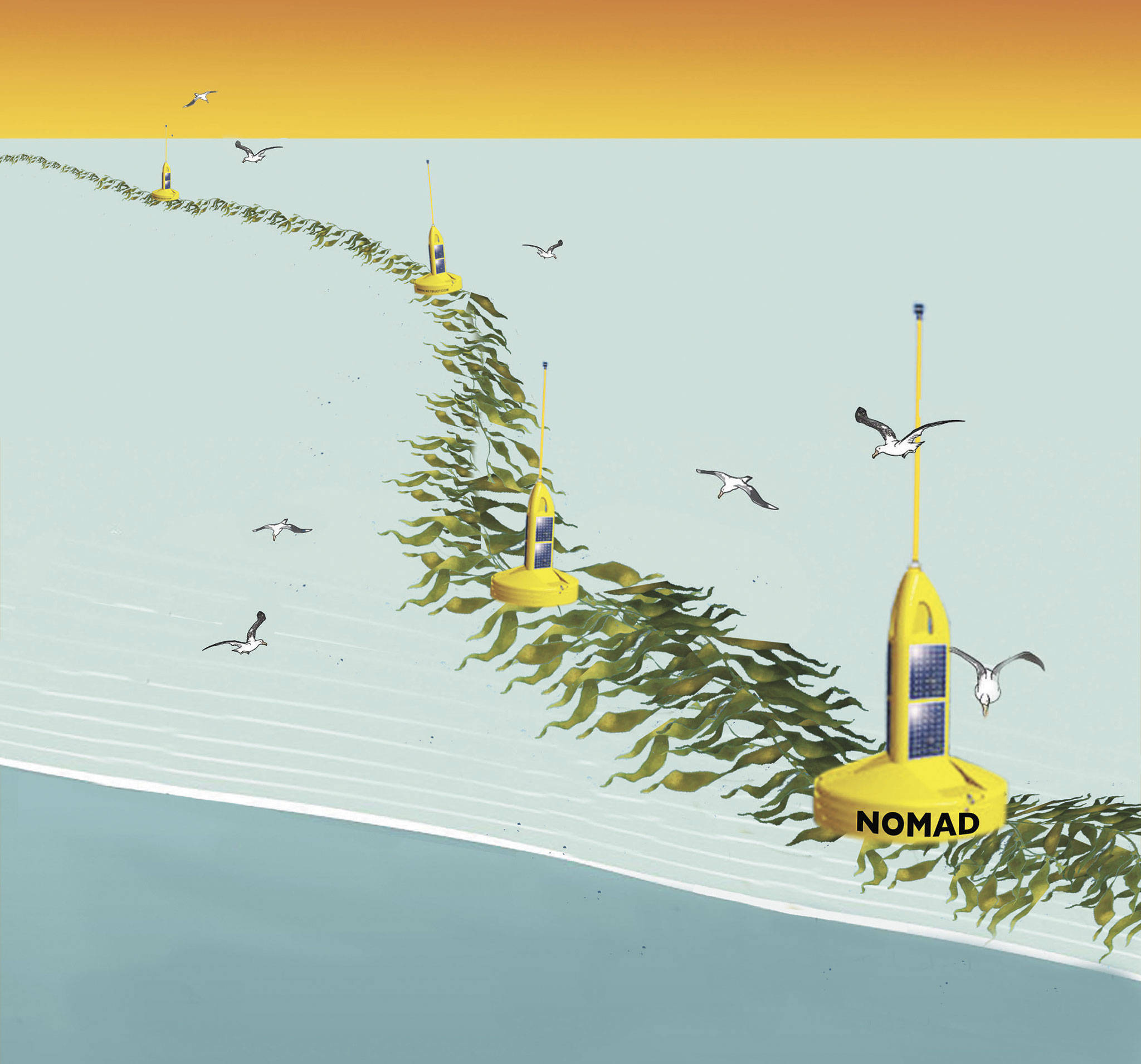

In 2018, Huesemann will lead the effort to design and produce the NOMAD system, or Nautical Offshore Macroalgal Autonomous Device, that will be deployed in Washington state waters with approximate 5-kilometer strands of carbon-fiber rope that cultivates seaweed in an open-ocean farm.

Using rope attached to navigation buoys with GPS sensors that track location, speed, light exposure and more, crews will deploy the strands offshore to follow the current to Southern California where boats will be ready to receive the rope and harvest the seaweed for biomass,” Huesemann said.

“It’ll be one 5-kilometer rope after the other — like pearls on a string — but NOMADs on a current,” he said.

Huesemann estimates the NOMADs could stretch as far as 1,500 miles.

PNNL officials said seaweed is primarily grown for human consumption but could become an economically viable renewable energy without using land, fresh water or synthetic fertilizers.

Officials with the Department of Energy estimate the U.S. could produce enough seaweed for about 10 percent of the nation’s annual energy needs for transportation.

To do so, however, scientists need to find ways to speed up production with materials such as carbon-fiber ropes.

New line

Huesemann said the autonomous seaweed collection system follows an effort 30 years ago to harvest seaweed off the coast of California. That project was anchored down but swept away by a storm. To work with the ocean rather than counter it, Huesemann and other researchers felt there should be a free-floating system.

Multiple agencies and learning centers are involved in the seaweed projects, including the Composite Recycling Technology Center in Port Angeles and Reliance Laboratories in Port Townsend.

Geoffrey Wood, Composite Recycling Technology Center fellow and vice president of innovation, said he and another engineer will develop the long carbon-fiber lines the seaweed will attach and grown on in the next year.

It’ll be made using scraps from aerospace carbon fiber materials such as wings.

“The reason we’re doing it is because if it was made of steel or metal it’ll sink, or a traditional marine-type rope will break down in short order,” Wood said.

He said the carbon fiber cables won’t degrade, can be heat-treated and steam-cleaned after the algae is removed, and be put right back in the water and begin the process again. “It’s a robust and durable system,” he said.

New systems

Jascha Gulden, CEO of Reliance Laboratories, has been tasked with the mechanical side of NOMAD.

His role comes in three parts, including developing the buoys with GPS tracking and an automated information system, the machines that place macroalgae seeds on the ropes, and the machines that harvest the seaweed at the end of cultivation.

“One of the big struggles of the whole project is hazard navigation so that we can have an autonomous system,” Gulden said. “We want to let any ship out there know where it is and how fast it’s going and where it’s going.”

Common commercial boats likely could be outfitted with the machines, Gulden said, to place and retrieve the seaweed lines similarly to crabbing gear.

Huesemann said the seeding machine will act like a sewing machine, attaching microscopic cells onto the line.

The rope will come in a big spool with three or four buoys per 5-kilometer line, Gulden said, and dropped into a current that runs to Southern California.

“Basically, we take this loose biomass in gigantic wads and we bring that onboard the vessel and turn it into something easy to grind up like a slurry into the boat’s hold and ready it for biomass production,” he said.

The harvesting machine will sheer the seaweed off, Huesemann said.

In the next year, Gulden anticipates a handful of his staffers working on it, including himself, two engineers and two laborers.

“We’re all proving ourselves and our concepts and the reality of those concepts,” he said. “I’m real confident we can get the hardware done.”

Huesemann said a Colorado State University professor will help determine the costs of the biomass production to match the Department of Energy’s goal of making it for $80 per dried ton.

Impact

Designing NOMAD, or phase one, was granted $500,000 by the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, ARPA-E’s Macroalgae Research Inspiring Novel Energy Resources program, or MARINER.

Huesemann said they’ll have until the end of 2018 to submit technical drawings and proof of concepts for a chance at additional funding and development.

Some of that will include the environmental impact, which he said should be minimal.

“With navigation on the buoys and GPS sensors, ships can be notified and (the ships or line) shouldn’t be damaged,” he said. “The other positive environmental impact is that fish could see this as an ecosystem and nibble on the seaweed is at floats along.”

Best seaweed

Huesemann’s team is one of two with PNNL working on biomass production with seaweed.

Zhaoqing Yang leads a team of six staffers in Seattle and two in Sequim to develop advanced modeling tools to determine where and when is the best time to grow seaweed on long lines in the open ocean.

Yang and his team were granted a little more than $2 million over two years to develop tools to evaluate seaweed growth potential, nutrient availability, and how natural phenomena such as wind, currents, tides, waves and storm surges could affect the productivity of man-made seaweed farms.

These projects have big supporters statewide including U.S. Senator Maria Cantwell, who visited the Sequim lab in July 2016.

“These grants are a critical part of our efforts to advance 21st century energy solutions and bolster the research done at PNNL-Sequim,” Cantwell said in September.

“By taking the long view of research investments in breakthrough energy and environmental sciences, we will ultimately make energy more affordable. We must continue to invest in research that matters and support the kinds of innovations brought to market by programs like ARPA-E.”

Huesemann said he and other project leaders will hold a kickoff meeting in Los Angeles at the beginning of the 2018.

For more about Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, visit http://www.pnnl.gov.