Big changes are coming.

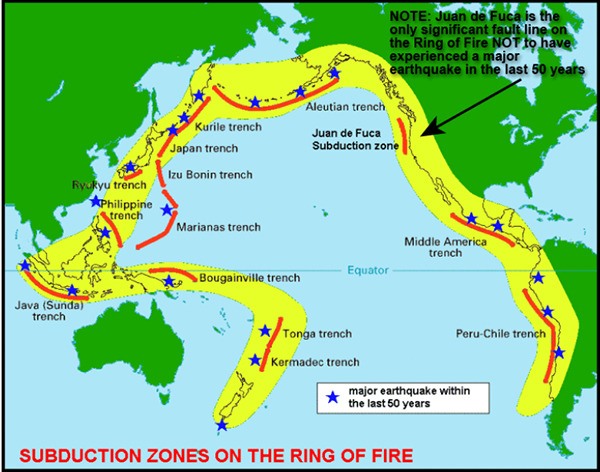

Paralleling the western coastline for about 800 miles from northern California to southern British Columbia, the heavy Juan de Fuca plate is slipping beneath the North American plate.

Through a variety of methods, modeling and ongoing research, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake, lasting 4-10 minutes is projected to occur at any moment and impact Sequim, along with all other nearby coastal communities as a result of the plate’s movement.

That reality has local and regional emergency management officials preparing for the worst.

“There’s no easy way to swallow the pill really,” Command Sgt. Maj. Steve Saunders said.

Historically, earthquakes have occurred along the fault every 300-500 years. The last recorded earthquake and corresponding tsunami was in January 1700. Secondary effects expected with a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami are landslides, avalanches, gas leaks, fires, flooding, hazardous material release, low level contamination in inundation areas, lack of food and water and disease.

Officials with Washington State National Guard anticipate nearly all hospitals, schools and senior centers within Region 2 (Clallam, Jefferson and Kitsap counties) to be destroyed and the event to leave thousands of people with little to no communication, electricity or means of transportation as all bridges are to be impassable.

Leaving standing room only, about 100 people attended a public briefing by Saunders on the Cascadia Subduction Zone and the guard’s associated Response Plan on Aug. 14 at the Sequim Civic Center.

Response plan under way

Because of the larger population and geographic proximity to the fault, Region 3, the counties south of Clallam and Jefferson counties are anticipated to be the most severely impacted. Although all coastal communities will endure damage, the severity is reflected in the guard’s Response Plan. Region 3 followed by those in the Seattle, Kirkland, Everett and Tacoma areas are to receive critical response attention first because of dense populations, leaving the Olympic Peninsula a lower priority.

“Being an isolated, rural community has its advantages and disadvantages,” Ben Andrews, Clallam County District 3 fire chief, said.

To effectively respond to the natural disaster, the Washington State National Guard is coordinating its efforts with many agencies, including those with the Department of Defense, multiple states and federal and state agencies, tribes and local municipalities and groups.

To streamline response time, Gov. Jay Inslee has pre-authorized the Response Plan, which can quickly be sent to the president for a final signature.

The next step to moving the plan forward is to conduct a full function exercise, known as Cascadia Rising, scheduled June 7-10, 2016. Spearheaded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the four-day exercise is intended to help train and prepare communities along the subduction zone by simulating field response operations. A variety of local stakeholders, such as personnel with the Clallam County Emergency Management, plan to participate in the exercise.

Self-preservation

Despite the Washington State National Guard’s Response Plan, given the scope of the aftermath from the rupture along the subduction zone, supplies and help are limited and self-preservation is anticipated to be key.

“There are too many people for how many assets we have,” Saunders said. “That is the reality.”

Reliance on airways for bringing in materials and aid will be vital following the earthquake given most roads and all bridges will be greatly damaged, Saunders said. Prior to safe passage for boats, all waterways must be remapped because things and the overall geography will have shifted beneath the water’s surface.

“The impacted routes and bridges will isolate communities,” he said.

The William R. Fairchild International Airport has been identified in the guard’s Response Plan as the main base and staging area, but because many bridges occur between Sequim and Port Angeles, Andrews doesn’t expect outside help or materials to reach Sequim quickly.

“Ten days is really the minimum now that you should be prepared to survive and be self-sufficient,” Penny Linterman, Clallam County Emergency Management program coordinator, said. “The best thing you can do is educate yourself on what you can do.”

Linterman suggest citizens begin preparing now by purchasing survival materials, like tarps, roofing nails for making repairs, fire extinguishers, a back-up supply of required medications, 5-gallon buckets, food and most importantly a water filtration system.

Linterman also encourages citizens to pursue locally offered courses such as the “Map Your Neighborhood,” a 90-minute class aimed at organizing neighborhoods to respond in the first hour of a disaster and/or CERT (Community Emergency Response Team) training.

“Most people survive the initial disaster, but it’s estimated about 40 percent get injured or die afterward,” she said. “Communication is going to be a huge issue, so that’s why we’re working from the neighborhood out.”

Among local entities, such as the county, fire and police departments, there’s an ongoing effort to best prepare for the earthquake, as well as a growing effort to coordinate and communicate with one another.

Already, Clallam County Emergency Management officials have upgraded two incident management vehicles, are working to stage resources somewhat evenly throughout the county, seeking connections with local faith-based organizations and hosting presentations and workshops in preparation for the Cascadia Rising exercise. Tsunami inundation maps are available through the county Emergency Management Program, however, updated versions are expected for release next year.

Fire district readies

Knowing Sequim is part of the larger Response Plan under way while also recognizing the area is fairly isolated and rural, Andrews is putting a lot of time and energy toward preparing.

“What we’ve learned from past experiences like the Oso disaster is that the fire department is what the community really relies on when something like this happens,” Andrews said. “We’re currently re-evaluating our emergency response plan.”

First, Andrews is focusing on the department by building up a backlog of fuel, food and a means of filtering water for his responders. Next, he plans to ensure both the department’s volunteers and staff are trained for such an event, however, Andrews feels fortunate to have a well-versed team already, including 10 crew members fully trained in incident management.

Just last year Andrews shadowed the incident commander and assisted in the response effort in Oso following a massive landslide. Additionally, three personnel from Clallam County Fire District 3 responded to Hurricane Sandy.

“We have some people with invaluable experience,” he said.

Eventually, Andrews envisions constructing a base camp for the responders on the department’s nine acres in Carlsborg.

“The Cascadia magnitude 9.0 earthquake is really the worse case scenario,” Andrews said. “If we use that as our model, we should be prepared for just about everything.”

Although Andrews is proactive in his preparatory approach, he reiterates and emphasizes the available resources and the ability to respond given the scope of the event are going to be limited and urges people to ready for self-preservation.

For more information on the mentioned courses and to learn more about what you can do, visit www.clallam.net/emergencymanagement or www.emd.wa.gov. To review the information presented by Saunders, visit www.commerce.wa.gov/Documents/APA-Eastern-WA-Planners-Forum.pdf.