by MARK ST.J. COUHIG

Sequim Gazette

Here it comes.

The Dungeness Water Management Rule, which has been in development for 20 years, the last four or so in earnest, has now been formally proposed.

The proposal was set to be released today, Wednesday, May 9, by the Washington Department of Ecology.

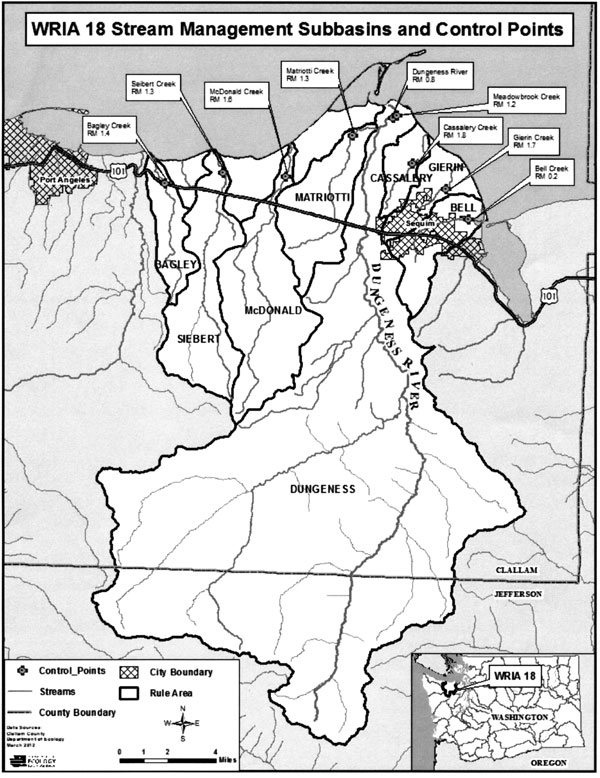

If it is adopted in August, as planned, it will put into place a new regulatory regime that covers much of rural eastern Clallam County.

Specifically, the rule calls for “closing” much of the Dungeness basin to new water uses.

The rule essentially would do away with the permit exemptions that now allow those who drill a well within the region to enjoy the resulting water at no cost. The existing exemption allows landowners to use the water for four purposes (see box).

The regulators say the rules are necessary because studies performed by the United States Geological Survey prove that removing groundwater via these wells reduces the flow of nearby rivers.

That water belongs to senior water rights holders. It also belongs to area Indian tribes, who under federal treaties have a right to fish and therefore a presumed right to sufficient water flow.

The rule doesn’t ban drilling; it says instead that those who drill wells would be required to pay to “mitigate” their use of water. They also would be required to put a meter on their well.

Current permit-exempt water users who engage in a “new use” of water also would fall under the rule.

The cost benefit analysis that accompanies the new rule was provided to the Sequim Gazette prior to its formal release. In the analysis, the agency attaches specific figures to the rule’s benefits, saying the avoided fish losses alone would be worth between $3.8 million and $6.8 million over the next 20 years.

The agency values each fish at $5,000 over 20 years.

The analysis also says the rule would ensure the benefits of the $20.5 million spent on past salmon habitat projects wouldn’t be lost.

Take it to the bank

Ecology officials say the rules will help those living and working in the affected area, and those who hope to do either, by providing greater certainty that water will remain available.

A water exchange will be established to serve as a mechanism to provide new water rights. The exchange, or “bank,” will serve as a conduit through which senior water rights holders can transfer those rights to new water users.

Gary Smith, an official with the Dungeness Water Users Group, recently said his organization may sell as much as 5 cubic feet per second through the exchange.

Because the exchange will provide a mechanism that will allow new users to purchase existing rights, the new rule is expected to have no negative impact on the flow in the Dungeness and in the other streams within the rule’s purview. Ecology says that’s an important feature of the new rule because it will reduce the possibility of lawsuits being brought by senior water rights holders, including the irrigators and the tribes.

The cost benefit analysis also puts figures to this benefit, saying the rule will save $2.4 million to $4.8 million by “avoiding legal costs” involved in a legal challenge and another $19.9 million to $62.1 million by providing “increased certainty in development.”

Ecology officials point out that before they can issue new water rights they must first ensure the water is both physically and legally available.

Because the water in the Dungeness basin is said to be “over-appropriated” — there are more assigned water rights than there is water — agency officials haven’t approved the issuance of new water rights since the 1990s. “We can’t in good conscience do that,” said Maia Bellon, water resources program manager for Ecology.

The costs associated with the rule are estimated at between $7.7 million and $23.1 million, with most attributable to the payments that will made by private land and homeowners as they mitigate for their water use. That includes, on the low end, $1.3 million to be paid by those drilling new wells and another $1.9 million anticipated to be paid by existing users who after initiating a new use will be subject to the rules.

If the population within the affected area grows significantly, the costs could be as much as $17.9 million for the new users.

Administering the new water exchange is expected to cost another $3.1 million.

Ecology Director Ted Sturdevant said he hopes the new rule proves the agency is making progress toward answering a “tough policy question.” He said as rural development conflicts with the stream flows required for a healthy fish population, and perhaps infringes on senior rights, the tension builds.

Bellon said, “We better have this sewn together to avoid the very heavy costs of not having it right.”

What does it cost?

The costs and benefits of the rule have been the subject of intense debate.

Internal Ecology e-mails obtained by the Gazette through a Public Records Act request show that Tryg Hoff, the agency economist who first drafted the Cost Benefit Analysis for the rule, said the costs could be as much as $500 million — far outweighing the benefits.

By law the benefits of a rule must be greater than the costs.

Hoff said he generated his analysis by including the decline in property values that will result when the right to drill permit-exempt wells is lost.

Hoff said the value of the existing right is substantial for every property owner because it includes all four uses — not just the right to use water inside the home, but also outside the home and an unlimited amount of water for livestock.

In one e-mail, Brian Walsh, section manager for policy and planning in Ecology’s water division, suggested to Hoff that in preparing his analysis he also should take into consideration the benefit that will result as the rule reduces the threat of litigation.

Hoff fired back, “I think we have two options here. 1. You can let me get more clarity to the baseline and let me do a legal analysis or, 2. You can direct me how to do the analysis. #1. Makes sense. #2. Is not lawful.

“If you are directing me how the analysis should be written, I would have to say you are asking me to break the law. This could be considered gross mismanagement and/or ignoring scientific evidence.”

The continuing debate concerns an interpretation of the law, with Walsh saying, “Because these properties do not currently have water rights associated with them, in the absence of an Ecology rule, if unmitigated new groundwater supplies were developed on these properties, the water supply would be at risk of being the subject of litigation and of being interrupted. Thus, without the rule, any new groundwater right would be of limited value to the landowner.”

Stephen North, an attorney with the Washington Attorney General’s office, said, “Folks may have an expectation that if they have property, they have a water right. But that is a false expectation. Any use before the rule (is promulgated) is a junior right.” Under the rule, “they’ll have rights to senior water.”

In his e-mail response to Walsh, Hoff added, “If you feel I’m not being properly obedient, or credible as a professional economist for this rule, I request you remove me from this rule immediately.

Hoff was soon thereafter replaced. E-mails describing the change stipulated that the change took place “at his request.”

The comment period on the proposed rule opened upon its publication today and ends July 9. A public meeting on the proposal will be held June 28 at the Guy Cole Center in Sequim.