Sequim’s iconic science facility now goes under a new moniker.

Overlooking Sequim Bay as the Marine Research Laboratory for the past 50-plus years, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) announced the facility was recently re-branded the Marine and Coastal Research Laboratory (MCRL).

“PNNL leadership, in consultation with (Department of Energy), determined renaming the laboratory was needed for it to reflect the laboratory’s expanded mission,” PNNL spokesperson Greg Koller said.

“The new name encompasses the laboratory’s past and current strong focus on marine sciences while noting it is building its programs and capabilities in the area of coastal sciences as well.”

In a recent article about the Sequim laboratory, Susan Bauer wrote that coastal zones make up 17 percent of the U.S. and contain more than half the population and nation’s economic and natural resources.

“Research and development for the coastal environment will become even more important as rising sea levels affect shorelines, ecosystems, groundwater, and infrastructure and as the nation looks to the ocean for energy, fresh water, and other natural resources,” Bauer wrote.

The Marine and Coastal Research Laboratory is the Department of Energy’s only coastal and marine sciences laboratory. Battelle, owner/operator of PNNL, purchased the historic site in 1966 and founded it as the Marine Research Laboratory.

Today, more than 80 researchers work on more than 100 active projects funded by government and private sponsors, Koller said.

“Sequim offers us many of the environmental conditions that are essential for PNNL to conduct marine and coastal research,” laboratory director Genevra Harker-Klimes said.

“There’s clean water and fresh air, a varied coastal environment and a community that’s supportive and collaborative.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many staffers continue to telework from home or other off-site locations and are not generally present on campus, Koller said.

On-site staff totals vary, with a maximum of 44 people allowed on campus daily, he said.

History

With most of its 100 acres remaining natural landscape, the laboratory sits atop the S’Klallam village site of sxʷčkʷíyəŋ, a site from which thousands of artifacts were discovered in 1981.

PNNL staff report a staff member found signs of cultural materials on the beach leading to the discovery of a prehistoric hearth carbon dated to the 1300s.

The archaeological recovery excavation uncovered more than 6,500 cultural artifacts that were given to the Clallam County Historical Society and then given to the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, Bauer reported.

In the 1800s, the village consisted of 10 longhouses, she reported, and is now registered as a Washington State Historical Place.

Hans Bugge purchased the future laboratory site in 1899 to open a cannery, The Bugge Cannery Co., which shipped local clams and clam nectar for more than 60 years until Battelle purchased the property.

A fire destroyed the remnants of the original cannery in 1972, Bauer reports, which led to the construction of wet labs and other research facilities.

The Sequim laboratory hosts more than 15,000 square feet of research space and delivers 200 gallons of treated seawater per minute to the bay.

Harker-Klimes said Sequim’s area is a draw for researchers.

“They are attracted by the combination of sea and mountains,” she said. “Recruiting is not difficult when you can offer them this kind of setting. It really is a beautiful place to live.”

She added that researchers support Sequim too with good paying jobs and the lab’s staff “are passionate about protecting the area’s environment, and are active in the community, supporting education, arts and many other organizations.”

Research

Of the dozens of ongoing projects, researchers continue to delve into producing energy and protecting the environment.

Helping eelgrass is one achievement Harker-Klimes notes as a continued priority for the lab.

Researchers say it provides habitat for shellfish and small sea animals, and for 20-plus years they’ve investigated how the climate has impacted its growth, how it grows best and where restoration efforts would be optimum.

Bauer reports researchers are delving into how changing temperatures and sea level affect eelgrass and interconnected habitats, such as where land and rivers meet the ocean.

Another project is the development of a natural wood-based product, an aggregator, that pulls and holds an oil spill together so it can burn specifically in low temperature areas like the Arctic.

Researchers in Sequim also study how marine energy projects could impact fish and marine life. A June 2020 PNNL article states scientists spent four years reviewing possible impacts and found it to be small or undetectable, but felt some uncertainty about some issues. They investigated issues from potential impacts such as underwater noise, and electromagnetic fields, but plan to continue to research and discover any impacts.

Along with protecting the environment, researchers look to harness energy from local waters with waves, seawater and more.

In late 2020, researchers revealed that the Pacific Northwest’s coastline waves hold promising areas to extract power and that waves could provide about 20 percent of the U.S.’s electricity needs.

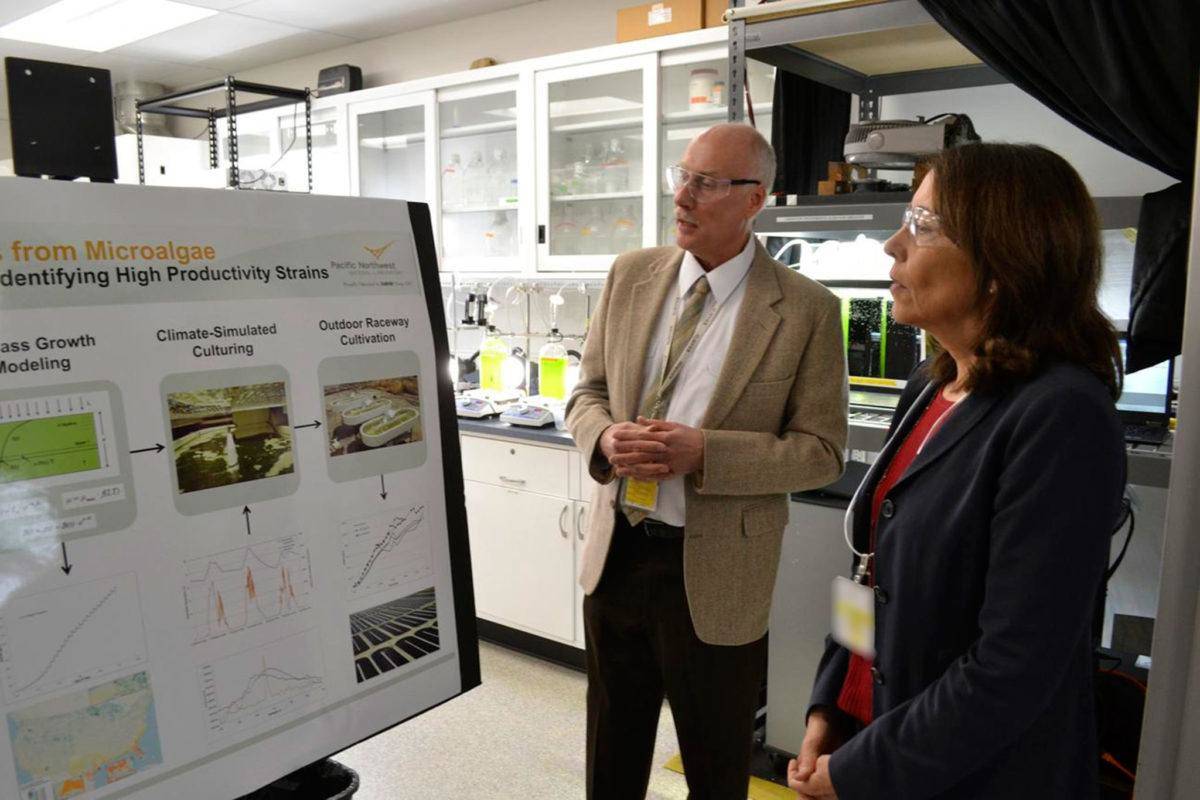

Work continues to find optimum ways to make biofuel from algae and extract minerals from seawater.

In 2018, researchers revealed they collected about five grams of yellowcake, uranium powder used for nuclear power production from seawater flowing onto treated yarn. At the time, scientists said it could provide an attractive nuclear fuel for reactors.

Efforts at the lab also focus on security for maritime commerce, coastal population centers and maritime borders, Bauer reports.

Researchers are developing technologies to sense, detect, and measure minute changes that can indicate threats, such as through acoustic signals, and chemical, biological, and/or radiological signatures, for potential terrorist threats.

For more information about PNNL and the Marine and Coastal Research Laboratory, visit pnnl.gov/marine-and-coastal-research-laboratory.

Watch a recent video about the lab here.