by MICHAEL DASHIELL

Sequim Gazette

Clint Jones is a man almost singularly obsessed.

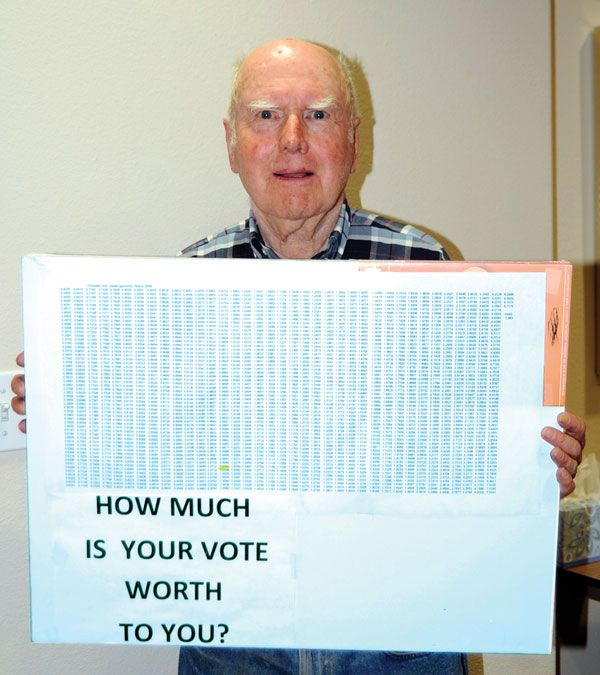

Between thick stacks of paper lined with numbers upon numbers, Jones records the statistics of every vote counted in every election since the Electoral College was put into practice in 1804.

Thumbing through these pages, the Sequim resident calmly but determinedly explains time and again that never — not once since its inception — have the Electoral College’s votes been valued appropriately and that several of the nation’s smaller states have been given disproportionate voting power when it comes to selecting the nation’s top executive.

“There are two classes of voters,” Jones says. He points to a chart listing the 50 states and the District of Columbia, their individual and electoral votes in the 2008 election, and another set of numbers: votes more or less than what Jones says their voting value should be.

He singles out three of the 47 presidential elections held since 1824, elections that would have seen the popular vote choose someone other than the candidate who was elected: 1876 (Benjamin Harrison versus Grover Cleveland), 1888 (Rutherford B. Hayes versus Samuel J. Tilden) and 2000 (George W. Bush versus Al Gore).

“A direct vote has nearly always equaled the College result. Those should have gone to the winner with the direct vote,” Jones says.

The Sequim resident insists a shift to the popular vote is not a political issue. Instead, he likens the Electoral College to a machine or instrument used in a crime.

“The First Amendment guarantees the right to an unabridged freedom of speech,” Jones says. “The Electoral College violates that right by intercepting and changing the values of our votes. We have become prisoners of our states.”

A disputed method

Conceived and first put into practice after its development in 1787, the Electoral College (as it was known by the mid-1800s) assigns a certain number of voters per state — and the District of Columbia — to vote for the next president of the United States. Electors are free to vote for anyone eligible to be President, but in practice they vote for specific candidates based upon the votes cast in their state.

Delegates from the union’s smaller states generally favored the electoral method because it kept larger states from controlling the outcome of general elections.

Over the years, the College has had its share of critics. Complicated elections in 1796 and 1800 fueled changes to the College. In the election of 1968, Richard Nixon topped Hubert Humphrey handily in electoral votes, 301-191, but by less than 1 percent of the popular vote.

A proposal called the Bayh-Celler amendment attempted to abolish the Electoral College, but failed by 1971.

When one vote doesn’t equal one

Because each individual state (and the District of Columbia) sees changes in population, the value of its Electoral College votes change as well.

Jones has tracked the value of each Electoral College vote since 1824. In 2008, he says, the American populace lost nearly 9 million votes in the presidential election because, thanks to the Electoral College, some states’ votes were undervalued and others overvalued.

The result, Jones indicates, is that some states hold a disproportionate sway with their electoral votes while others, including Washington, “lose” their Electoral College voting power and subsidize other states.

By Jones’ calculations, Washington has lost more than 3.5 million votes worth of election power since 1892.

Since 1964, there have been 538 electors in each presidential election; in 2008, each elector was worth the equivalent of 244,011 votes cast. By Jones’ calculations, the Electoral College is off by nearly 7 percent. Part of the problem is that the Electoral College is based on census data — and generally outdated data at that — and that it uses figures regarding total population, not registered voters.

“Certain people have an advantage in this,” Jones says. “Why fight each other state by state? It should be like that.”

So what’s the answer to the incongruity and unfairness as Jones sees it? Easy. Executive order, he says. The president can by his own order move to declare the election of the president by popular vote rather than by electors. Executive orders do not require congressional approval, he notes, so the president can use them to set policy while avoiding public debate and opposition.

Jones says he suspects this action won’t take place without some effort and he’s looking for some help toward getting legislators to take notice of the issue.

Contact Jones at 681-0101 or by e-mail at clintjones@olypen.com.

For more information about past U.S. Presidential elections, see www.americanpresidency.org/elections.

Reach Michael Dashiell at miked@sequimgazette.com.