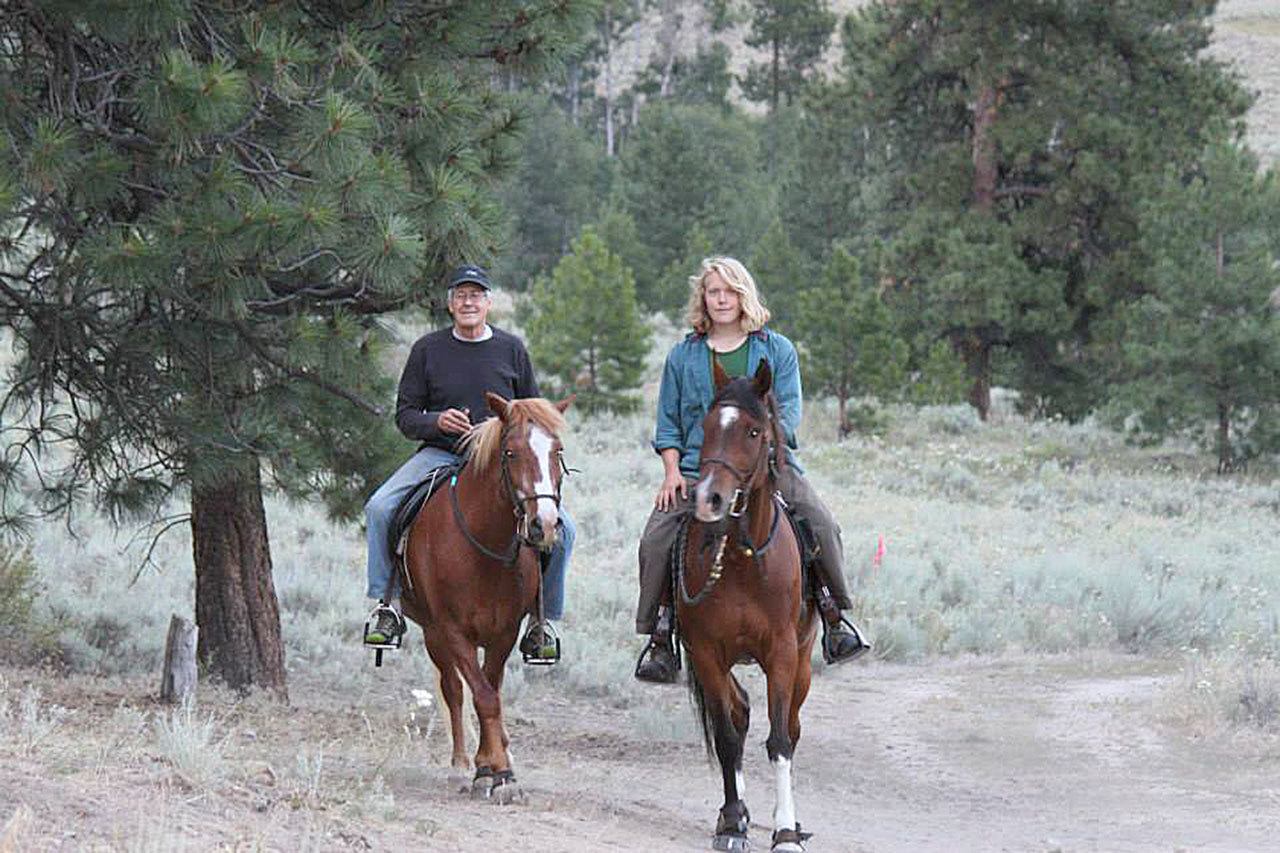

Bill Jevne, 72, and his son William Jevne, 24, of Sequim, traveled to the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota from Dec. 3-4, to donate supplies and show their support for protesters against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Bill, a Marine Corps Vietnam veteran, said it was his patriotic duty to help stand up with others for the Standing Rock Tribe that is trying to protect its water and its land.

“They were not significantly involved in the planning for the pipeline,” Bill said. “As a result, a plan came along that was threatening to them, when it could have been done another way.”

Bill Jevne said tribal members felt like they were being treated in a marginalized way and that it was important for the tribe to stand up.

William said he had been thinking about going to Standing Rock after hearing about the protests from friends and activists who had been to the site, but when the van he was going to take broke down, his father called and he decided to travel with him, helping him transport sleeping bags, food and a Mongolian yurt that was purchased for the on-site medical camp at Standing Rock.

Juanita Ramsey-Jevne, Bill’s wife, also played a role in the Jevnes’ experience by following the Standing Rock protests, organizing donations to give to the Standing Rock Tribe, and contacting the medical camp at Standing Rock where the yurt was needed.

The Jevnes arrived at the main camp at the north side of the Cannonball River. William said it was bigger than he realized, resembling something the size of a festival such as Burning Man.

“When I got there, there were a bunch of people arriving and it was really busy,” he said.

Bill said from the moment they arrived at the campsite, they were informed that this was to be a peaceful and non-violent protest.

“It is the tribe that is running the show and we are here in prayer,” he explained, saying how everyone was respectful of the tribe’s codes of conduct.

William said he spent the first day of camp helping with the construction of shelters for veterans, while Bill rested because of back problems.

The camp had a working infrastructure, the Jevnes said, including porta-potties available for sanitation, firewood, doctors, a medical unit and even a legal team.

An orientation was provided for those who arrived and gave them basic information on where to get necessary resources such as food and shelter, and how to keep warm.

The camp also provided mandatory direct action training, the Jevnes said, explaining how protesters were to conduct themselves.

The codes of conduct included non-violent practices and physical tactics for resistance. Participants also were informed of their rights if arrested.

“It’s a prayer, not a protest,” William said, explaining the essence of direct action training.

He said there were very specific guidelines when it came to those who protested at the bridge and had direct confrontation with law enforcement. Some of the codes of conduct included not aggravating law enforcement and advised against actions like shouting slurs and throwing objects.

“I think you can argue the merits of the pipeline all day, but having people who are able to take more positive action to protect their interests,” was the takeaway from the experience William said.

Though Bill said most of his time at Standing Rock was on his back because of his injury — one that limited his and William’s time there — he said he believes the way things were being done at Standing Rock is “an example and an inspiration” for the way protests can be done in the future.

As a Vietnam veteran, Bill said he is a patriot to the core. But during his service, he felt the government got it wrong in the actions it took and said many Iraq and Afghanistan veterans feel the same way.

“If (the government) would have broken up the camp at Standing Rock, they would be getting it wrong again,” he said.

Bill said that part of patriotism is examining the decisions the government makes and taking a stand, and showing solidarity as veterans at Standing Rock is a way to express his and others’ patriotism.

Peninsula residents stand with protesters

Determined protesters who were ready to dig in for the winter broke out in celebration Dec. 4 when the news was announced that the Army Corps of Engineers would deny access to the Dakota Access Pipeline through the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, said Meri Parker of the Makah Tribe.

“When the news was announced today, there were tears of joy, tears of disbelief,” said Parker of Neah Bay.

“The reaction has been overwhelmingly jubilant,” said Parker, a former Makah Tribal Council member and general manager. The way to victory, Parker said, “was to be peaceful and prayerful and standing for the cause.”

Port Townsend resident Doug Milholland was with protesters at the reservation in North Dakota when the news was announced, said his wife, Nancy Milholland. He had called her when he heard the news, she said.

“He’s just thrilled,” she said Sunday afternoon.

Megan Claflin, spokesman for a group of 30 people who took food and supplies to Standing Rock from Port Townsend on Nov. 21 and returned Nov. 27, was celebrating in Port Townsend.

“My immediate reaction is a sense of victory, an affirmation that our peaceful, prayerful efforts were successful,” Claflin said, while adding that it might be a temporary victory.

The Wall Street Journal noted that President-elect Donald Trump has said that he supports the Dakota Access pipeline.

At Sunday’s Jefferson County Democrats meeting in Port Townsend, a roar rose up from some 200 people when chairman Linda Callahan announced the news.

“Our voices matter. Our voices are heard,” Callahan said after the cheers subsided.

“I get a lot of hope,” added former Jefferson County Democrats chairman Matt Sircely, “from the solidarity around Standing Rock.”

Pipeline, ‘sacred land’

Parker said an estimated 10,000 people were camped in opposition to the plans by Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) to build a pipeline across Sioux sacred land and under Lake Oahe, a Missouri River reservoir in southern North Dakota.

Protests began months ago, after Sioux leaders said that the pipeline threatened sacred sites and told of fears that a leak could contaminate drinking water.

“More than 300 tribes have been represented here, indigenous people from all over the world,” Parker said.

“We have 4,000 veterans here, too. All these veterans have literally deployed here. It’s an amazing scene.”

Parker said that one reason she joined the protest in North Dakota is because of the risk of oil spills that the Makah feel in their position at the northeast corner of the state.

“Tanker traffic passes by our front door every day,” she said. “It makes a difference. It’s meaningful to me to be here. I’m so thankful for the opportunity to be here today and stand in solidarity with the Standing Rock Tribe.”

The pipeline is being built to transfer oil from North Dakota’s Bakken region through South Dakota and Iowa into Illinois. The $3.7 billion pipeline would transport about 470,000 barrels of domestic crude oil a day.

The 1,200-mile, four-state pipeline is largely complete except for a section that would pump oil under Lake Oahe, a Missouri River reservoir in southern North Dakota, The Associated Press has reported.

Assistant Secretary for Civil Works Jo-Ellen Darcy said in a news release that the Corps must “explore alternate routes” for the pipeline’s crossing. Her full decision doesn’t rule out that it could cross under the reservoir or north of Bismarck.

“This is a small victory in a bigger fight,” Claflin said. “What does this mean? It doesn’t mean that the pipeline’s dead. It means that the process will be longer.”

Paul Magrid, who with Daniel Milholland led a caravan of some 30 people to Standing Rock carrying donated food and supplies, said the decision was “a great victory. It’s tempered by the fact that it’s not a permanent victory. The fight’s not over.”

Said Claflin, “The point is to stop it going through the reservation and to raise awareness of the greater issue of energy independence and sustainability as a community.”

She said the group is preparing a presentation on members’ experiences at Standing Rock on an as-yet-determined date later this month.

Parker said that she didn’t know how long protesters would remain on the tribal land.

“I’m not in that loop,” she said. “But we’ll probably stay here until the construction workers are gone, until it’s believable.”

Peninsula Daily News Executive Editor Leah Leach, PDN reporters Cydney McFarland and Chris McDaniel, and freelance writer Diane Urbani de la Paz contributed to this story.